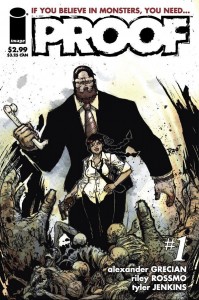

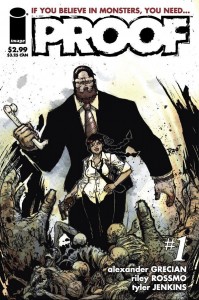

Behind the smile and friendly demeanor of Alex Grecian, there must lie some deeper, darker demons. After all, this is a writer whose Image Comics’ series Proof is steeped in conspiracy theories, ancient monsters, and characters who die before their times.Proof

We caught up with Alex at the MO-KAN Comics Conspiracy show in Kansas City in the fall of 2008. During our interview, Alex didn’t really hint at any sinister past, though. Instead, he talks about his background in advertising, design, typography, comics art, and his eventual transistion into full-time comics writer and novelist. Not a hint of a demon.

You can read the first issue of online for free at the Image Comics site.

Kansas City Comics: Tell us about Proof.

Alex Grecian: Proof is an ongoing series about The Lodge, a top-secret government organization jointly funded by the US and Canada. The Lodge is headed by a mysterious man named Leander Wight whose goal is to ensure that humans and cryptids live in harmony.

Cryptids are monsters that might actually exist, creatures that have been witnessed, but never caught: The Loch Ness Monster, El Chupacabra, The Mothman, Bigfoot,… all cryptids.

Speaking of Bigfoot, The Lodge’s star agent is a sasquatch. He’s the only non-human agent and he goes by the name John Prufrock. His friends call him Proof for short. He’s a stylish guy who cares deeply about his appearance and manners, but for obvious reasons he can’t interact with the public.

Proof’s partner is Ginger Brown. She was a rookie FBI agent and was recruited by The Lodge after she met a golem while on a case in New York.

Other agents include Elvis Chestnut, who came to The Lodge after his mother was killed and inhabited by El Chupacabra; Wayne Russet, Proof’s best friend and lead cryptozoologist; and Noel Russet, Wayne’s estranged son.

Other agents include Elvis Chestnut, who came to The Lodge after his mother was killed and inhabited by El Chupacabra; Wayne Russet, Proof’s best friend and lead cryptozoologist; and Noel Russet, Wayne’s estranged son.

The first story arc [issues 1-5] was collected in the Goatsucker trade. In it, we’re introduced to all these characters, plus an agent named Autumn Song, who isn’t terribly nice, but is good at her job. The second arc [issues 6-9] is called The Company Of Men

trade. In it, we’re introduced to all these characters, plus an agent named Autumn Song, who isn’t terribly nice, but is good at her job. The second arc [issues 6-9] is called The Company Of Men , and will be collected this December. That book takes the Lodge agents to Africa in search of a baby dinosaur, then to Seattle to find Elvis a new suit.

, and will be collected this December. That book takes the Lodge agents to Africa in search of a baby dinosaur, then to Seattle to find Elvis a new suit.

Currently, Proof is in the American Midwest, dealing with giant thunderbirds, in the arc Thunderbirds Are Go, which also follows Ginger back to New York to wrap up loose ends in her life there.

Kansas City Comics: How did the idea for the series come about?

Alex Grecian: A friend of mine made a joke about the reason why nobody’s found Bigfoot: The CIA already found him and he’s working undercover. It didn’t sound like a joke to me. It sounded like a great idea for a story. As I began to explore what Bigfoot would want and why and how he’d work for the government, the idea took shape, layering over itself like a pearl.

Kansas City Comics: How did you connect with artist Riley Rossmo? What added elements has Riley brought to the series?

Alex Grecian: Riley and I did a graphic novel called Seven Sons for AiT and enjoyed working together. When we finished Seven Sons, we started casting about for something else to collaborate on. As soon as I started thinking about Proof – and long before I had a title for the series – he was the first and only artist who came to mind. Fortunately, he immediately saw as much potential in the idea as I did.

for AiT and enjoyed working together. When we finished Seven Sons, we started casting about for something else to collaborate on. As soon as I started thinking about Proof – and long before I had a title for the series – he was the first and only artist who came to mind. Fortunately, he immediately saw as much potential in the idea as I did.

To make a series like Proof remotely believable, as opposed to cartoony and silly, the characters need to seem like real people. Or as real as a comic book about Bigfoot can get. Riley’s work stands out in many ways, but the thing I like most is his ability to convey facial expressions and body language in a way that allows the characters to communicate without dialogue. That makes my job much easier. He really breathes life into Proof and the supporting cast.

Plus he’s impossibly fast!

Kansas City Comics: Over the first dozen or so issues of Proof, have you found that the series has diverged from your original plans?

Alex Grecian: In some ways. We started out with a rough blueprint for the entire series and that’s still intact. The ending for the series will still be what it’s always been. But we went in with a lot of wiggle room to explore things along the way and that’s allowed us to have fun and discover aspects of the characters and situations we didn’t anticipate.

Kansas City Comics: What surprises have come up along the way?

Alex Grecian: There’ve been a couple of characters who were supposed to die or disappear and they’ve come back. Elvis Chestnut in particular took on a life of his own and has become integral to the resolution of the entire series. Originally, he was going to be eaten by the chupacabra in issue two. The final issue of Proof, though, would be much less satisfying without him, so I’m glad he’ll be around to contribute to it.

Kansas City Comics: What other projects do you have in the works?

Alex Grecian: I have a series of all-ages graphic novels coming out, with Kelly Tindall on art. They’re called Squeak! The bizarre adventures of a pet mouse. They’re a lot of fun.

I’m also hard at work on a mind-blowing miniseries called The Colony, a children’s book, and a couple of other things that I probably shouldn’t talk about yet.

Kansas City Comics: How does your screenwriting and prose work affect your comics work?

Alex Grecian: They’re night and day, really. Writing for comic books is much more difficult and restrictive than, say, writing novels or short stories. At least for me. My tendency is to want to explore every avenue that presents itself with a character and you have that freedom when you’re writing a novel. As long as the structure is sound, you really don’t have to worry about how many pages are in a chapter. But in comics, you’re constantly watching the pace, making sure you can fit everything you need in those 22 pages for an issue. Plus, each page is like a chapter, where you’ve got to be aware of your beats and have a mini-beat fall at the end of the page, prompting the reader to turn to the next page. It’s much more challenging for me and a reason I think a lot of novelists don’t do well when they make the transition to comics. Of course, many do, but some are probably turned away by the demands of the medium.

The upside, though, is the collaboration. If I’m working with a really good artist, someone like Riley, I get to see the story filtered through him and that gives everything a new dimension it wouldn’t otherwise have. I love it.

I’ve only written one movie treatment and hated every minute of it. That was an adaptation I was asked to write by a production studio and the source material was a terrible comic book series. I agreed to do it before I read the comic and then my heart sank once I actually got the thing and started taking notes. I’d like to take another stab at a screenplay one of these days, writing an original story or adapting something of my own. But the challenges there are tenfold what they are in comics. If you’re not careful, I think the story can take a backseat to the demands of the medium and you get kind of lost.

For now, I’m really happy writing comics and crime novels.

Kansas City Comics: Do they cross pollinate in some fashion?

Alex Grecian: Each kind of rejuvenates my creative batteries because I’m exercising different muscles. But writing novels taught me to sit down and write at the same time every day and set a goal for myself. That’s become my routine and without it I wouldn’t be able to get much done.

Kansas City Comics: I think it’s interesting that you’re also the book’s letterer. As a writer, what are the benefits of having that level of control on the placement of your words?

Alex Grecian: Oh, it’s enormous, really. It’s helped us to remain on-schedule, for starters. I don’t have to sweat the dialogue too much, so Riley never ends up waiting on me for scripts. The script I send Riley is pretty detailed, but I don’t take the time to go back and choose the words in the dialogue, write another draft of it. Once I get the art back from Riley, I can make my tweaks and reposition things to match the art well and help the flow and pacing. That’s also the point at which I realize Proof wouldn’t have phrased a certain sentence the way I first wrote it, etc. I love being able to have that one last swipe at things before it all goes off to the printer, a final draft on the page.

I do hate doing the sound effects, though. I cheat on those quite a bit.

Kansas City Comics: I understand that you also create fonts. That’s an unusual sideline for a writer. How did your typography work come about?

Alex Grecian: I became fascinated with fonts when I worked as a pager – that’s someone who lays out publications – for a printer-publisher. They had hundreds, maybe thousands, of fonts on their servers because each magazine they published used a different set of typefaces. But there was no organization to any of it, so in my spare time I put together a font library for them, consolidating everything and learning a lot about fonts as I went along. They used a program called Fontographer to fix damaged fonts and I gradually taught myself how to use that software to make all-new fonts. That eventually turned into a sideline for me.

Kansas City Comics: How has your background in advertising affected your comics career?

Alex Grecian: I started as an illustrator and idea guy. I was headhunted after doing freelance work while I still worked for that publisher I mentioned. I was a busy guy. From there, I was able to move into just about every aspect of ad work, except sales and media buying. I wrote copy, gave presentations, and managed to work my way into directing TV spots. My primary function, though, was to brainstorm new campaigns for clients.

Learning to storyboard for TV and hit deadlines definitely helped me think visually and put a book out on time every month. It was incredibly useful training.

Kansas City Comics: What made you decide to leave advertising and write full time?

Alex Grecian: Well, I started to hate my job. The country was going through a recession and about half of my co-workers at the agency were laid off. The atmosphere became extremely political and onerous. I was also stupid enough to sign a non-compete contract when I started there that specifically kept me from doing comic book work. At first that wasn’t so bad because I was so busy I didn’t have time to even think about comics. But the less happy I was at my day job, the more I wanted to write my own stories as a creative outlet.

When my wife got pregnant, we both wanted our son to have a stay-at-home parent. My wife had a better-paying job, I hated my job, and it seemed logical that I could freelance from home.

The original plan was for me to be a freelance advertising illustrator. But I started writing comic book pitches and scripts and before we knew it I was working full-time to break into comics as a writer. I guess I just finally decided I wasn’t going to have any more opportunities to follow my dream. And I was awfully lucky to have such a supportive spouse.

Kansas City Comics: How did your early work in The Factor, 24 Hour Comics, and Seven Sons come about? What did you learn from those projects?

Alex Grecian: I was introduced to Nat Gertler at a convention when he was looking for artists. I had a portfolio because I was drawing my own stories and he invited me to draw a couple of projects for him, including The Factor

at a convention when he was looking for artists. I had a portfolio because I was drawing my own stories and he invited me to draw a couple of projects for him, including The Factor and Licensable Bear

and Licensable Bear . I also wrote and drew a 24-Hour comic, somewhere in there, and turned it into a mini-comic, which I sent around to creators and publications. CBG gave it a glowing review and for a while it looked like I had a shot at breaking into comics. But, then I went to work for the agency that wouldn’t let me do comics work.

. I also wrote and drew a 24-Hour comic, somewhere in there, and turned it into a mini-comic, which I sent around to creators and publications. CBG gave it a glowing review and for a while it looked like I had a shot at breaking into comics. But, then I went to work for the agency that wouldn’t let me do comics work.

When Nat put together the first 24 Hour Comics book – which was edited by Scott McCloud and included stories by Neil Gaiman and Stephen Bissette – I was fortunate to have Scott choose my story for inclusion. That encouraged me to go after comics work again.

book – which was edited by Scott McCloud and included stories by Neil Gaiman and Stephen Bissette – I was fortunate to have Scott choose my story for inclusion. That encouraged me to go after comics work again.

Mostly what I learned from those projects was that I shouldn’t draw. And if you’re trying to carve out a career, you shouldn’t lose your forward momentum. By disappearing entirely for a five year period, I ended up having to start all over again.

Seven Sons was a different deal altogether and came much later, after I quit the agency. I decided I really didn’t have the chops to draw comics and should just stick to writing. I’d met Riley Rossmo and sent him a list of, I think, 16 story ideas. He picked Seven Sons and we put together the graphic novel together, which we sold to the first publisher we approached: AiT. We kept our momentum and used Seven Sons to help us sell Proof to Image.

Kansas City Comics: Nat Gertler seems to have had a major impact on your early career. Tell me about his influence, and others who have had an important role in your development.

Alex Grecian: Nat’s a great guy and was very good to me. It was useful to draw from someone else’s script because I learned some of the fundamentals of formatting. But I chafed at having to draw someone else’s stories and basically figured out the hard way that drawing wasn’t the part of the process that I liked. Poor Nat didn’t get my best work. I really wanted to be doing what he was doing, not what I was doing.

I was lucky, early on, to have a number of people who encouraged me and gave me confidence. Batton Lash, who writes and draws Supernatural Law , and his wife, Jackie Estrada, who runs the Eisner awards, were terrific. They saw some potential in me, I guess, and introduced me to lots of other comics folks. My wife and I even stayed in their home on our honeymoon! Ande Parks and Phil Hester gave me tons of advice and some early opportunities. My first published work was as an uncredited inking assistant on a Caliber book Ande inked. Paul Fricke, who co-created Trollords and inked a ton of DC stuff, was also a great source of advice and became a good friend. Dave Sim and Eddie Campbell also took time to talk and write to me and help me figure things out when I was just starting out. And Brian Wood actually gave Riley and me the introduction to Image that led to us pitching Proof.

, and his wife, Jackie Estrada, who runs the Eisner awards, were terrific. They saw some potential in me, I guess, and introduced me to lots of other comics folks. My wife and I even stayed in their home on our honeymoon! Ande Parks and Phil Hester gave me tons of advice and some early opportunities. My first published work was as an uncredited inking assistant on a Caliber book Ande inked. Paul Fricke, who co-created Trollords and inked a ton of DC stuff, was also a great source of advice and became a good friend. Dave Sim and Eddie Campbell also took time to talk and write to me and help me figure things out when I was just starting out. And Brian Wood actually gave Riley and me the introduction to Image that led to us pitching Proof.

This industry’s full of generous people. Networking’s important in just about any field, but it’s probably easier in comics because there are so many gifted people who are willing to share their time and knowledge.

Kansas City Comics: When did you first begin creating comics?

Alex Grecian: I can’t remember. My son’s been drawing his own comics since he was two, so I imagine I started at about the same time.

Kansas City Comics: What was your family situation at the time, and did that affect your interests in comics?

Alex Grecian: My dad’s always read comic books. One of my earliest comic book memories was sitting at the dining room table, reading my dad’s copies of the Warren Spirit reprints. So, yeah, having comics around and having a parent who’s a professional writer, I guess it’s not hard to put two and two together.

Kansas City Comics: What were your biggest early influences?

Alex Grecian: The first comic I can remember picking apart and examining to see how the creator did what he did was The Spirit. Eisner was, and is, a huge influence. Peanuts was a big deal for me too.

Probably the most influential early comic for me, though, was an issue of DC’s Showcase that heralded the “new†Doom Patrol. I’d never heard of The Doom Patrol before, but it was clear that it was a team that’d been around since long before I was born. And the whole team (with the sole exception of Robotman) got killed in that issue. Here I’d just found out about these weird characters and they were suddenly gone. That was huge for me. The idea not just that comic book characters were mortal, but that continuity could move forward and things could change. That’s an exciting idea.

And it may be why I still have a tendency to kill off characters as soon as I start to get attached to them. Riley’s saved several Proof characters from certain death.

Kansas City Comics: From where do you currently draw your inspiration? What do you do to recharge your creative batteries?

Alex Grecian: Personally, I like to write in more than one medium to keep things fresh. I’m desperately trying to carve out some time to finish my third crime novel, which I think is the most ambitious project I’ve ever written.

Kansas City Comics: Ambitious in what way?

Alex Grecian: When comic book writers try their hand at writing prose, they tend, at least in my opinion, to overcompensate for the lack of pictures and end up writing horrible, flowery stuff. Neil Gaiman’s an exception, of course, and I’m sure there are others. But the two media exercise completely different creative muscles and that takes some adjustment.

Anyway, my first prose novel was kind of a mess and I put it away. It’ll never see the light of day. The next two I wrote were much better, I think, leaner and more focused. I’m really proud of them. This third (or fourth, depending on how we count them), is written in the first person, which is trickier than third person perspective, and it’s much darker and more serious. I’m trying to tackle some big issues, within the context of a detective novel. Hopefully I’m able to pull it off, but working on it is honestly exhilarating.

Kansas City Comics: What is it about comics that appeals to you as a creator?

Alex Grecian: Writing a book is a solitary experience. So is writing a comic book script, but then someone else takes that script and turns it into something else. I guess I love the collaboration more than anything. And that really doesn’t apply to writing. I have no interest in collaborating with another writer. I like seeing my work taken to another level, though, that process of transforming it into another art form.

Kansas City Comics: Describe your typical writing routine.

Alex Grecian: I get up between five and five-thirty every morning, seven days a week. I drink a pot of coffee while I read and respond to email, check the Proof message board and catch up on the day’s news. Then I get to my desk before the sun’s up and start writing. I usually leave off between scenes so that I can think over the next day’s scenes later in the day when I’m not writing.

My wife comes down a little after seven and I send her off to work then get my son up and ready for school. After I take him and get back home, I eat breakfast and then get back to work. In the afternoon, I do production work, color-correcting Proof pages, writing letters and pitches, lettering and putting together back-matter. Then I pick my son up from school and I’m just dad, taking care of him and making dinner. It’s a nice routine.

I try to pattern my life after the main character, a writer, in The World According to Garp. That was my favorite novel for a long time and another big influence on me.

Kansas City Comics: What is the typical starting point of a story for you?

Alex Grecian: The vast majority of my writing time is spent trying to figure out where to begin and end scenes and massaging the transitions between scenes. Every scene starts for me with the characters, thinking about what they want and what they’re trying to get accomplished in that scene. The characters are always the starting point. In fact, I began my third novel with no plot and no idea where I was going, just the relationship between two brothers, one of whom is learning disabled, and the detective agency they inherited from their father. I love exploring what makes people tick.

Kansas City Comics: How do you judge when a story is “done” and you can stop revising it?

Alex Grecian: When Riley calls and says he needs more script pages. [Laughter]

Kansas City Comics: What’s the most common advice you give to others who want to work in the comics industry?

Alex Grecian: It might be presumptuous for me to give advice at this point in my career, but since you asked…

I’ve got a long two-part answer, but it really all boils down to a single word: write!

I think too many aspiring writers give too much weight to ideas. They treat ideas with reverence. An idea is just the first step in a story. And the easiest step. It’s a tool to get you into the process. If you want to write, you’ve got to get your hands dirty and actually write.

An aspiring writer came up to my table at a recent con and asked for some advice. He’d spent years working out his epic comic book series and he was stuck. It sounded like he’d been stuck for a while and he wanted to know how to break past whatever roadblock he’d run into so he could keep going with his masterpiece. My advice to him, which he clearly didn’t appreciate, was that he should abandon it and move on to another story.

Since Proof started up, I’ve had a fair number of people email me with this same problem and I always say the same thing. Being a writer is about writing. Yes, absolutely, you’ve got to work through story problems. But if your story is growing barnacles instead of actually moving forward, then you’re not writing, you’re just mulling something over.

It’s much easier to build an epic in your head than it is to sit down and build individual scenes and characters. But without those things, you don’t have a story.

And if you’ve only got one story to pitch to companies, your chances of breaking in aren’t swell. I spent three years writing at least one new pitch a week before a single one of them was picked up by a publisher. Some of those were pretty good, but they didn’t meet the editorial needs of the publishers I sent them to and they were rejected. If I’d put all my eggs in one epic basket, I’d still be spinning my wheels now.

The second part of my answer ties into the first, really. You’ve got to sit down at a specific time every day and write something. If you’re stuck at some point in your masterpiece, you’re not gonna get much actual writing done. After a few days of that, you’re probably not gonna bother to sit down at your computer or your typewriter or your yellow legal pad. And if you’re not writing, you’re not a writer, are you?

When I write a novel, I set a daily goal of 2,000 words. When I write a comic book script, I aim for two complete scenes a day, however long those may be. I don’t always reach those goals, but there have been days in which I’ve exceeded them, so I know it’s possible. There’ve also been days in which everything I’ve written has been worthless, but it’s important to sit down and do the work. You can revise or trash your day’s work later.

Writing’s a job and I think you have to treat it like one. If you sit around and wait for your muse, she may not show up. You’ve got to force her to show up by sitting and typing or writing longhand, if that’s your preference.

Kansas City Comics: What are the biggest mistakes you’ve seen other creators or aspiring professionals make that hurt their chances to advance their careers?

Alex Grecian: I’m really going to come across as arrogant when I attempt to answer this. Hopefully I don’t completely disappear after I shell out advice about other folks’ careers.

Again, I think it’s a big mistake to bank on a single idea or story or series. Or medium. Brian Bendis has pointed out that, no matter how popular a creator is, he or she usually has a shelf-life. I could point to several creators who were huge at one time, but who’ve virtually disappeared from comics now. I think we should all keep as many oars in the water as possible. If you’re doing a company-owned book, you should also be doing a creator-owned book. Besides, I’m a big proponent of creator-owned books; that’s where this industry gets fresh ideas, new talent and passion. If you’re writing comics, you should also be writing novels or short stories or plays or films. Or all of those.

But I don’t think you should abandon one medium for another. If you’re trying to break into comics, you should be doing it because you love comics, not because you think it’ll be easy. It’s not. Comics shouldn’t be a stepping stone to another medium.

If you are lucky enough to break into comics and make a name for yourself, it’s important to remember that somebody’s reading what you’ve written. You owe that readership your best work, every single time.

When it comes to aspiring professionals, the biggest mistake I think you can make is to give up. You’re going to be rejected again and again. Even after you break in, you’re going to get some rejection. Develop a thick skin and keep moving. Writers are like sharks. You have to keep swimming or you’ll die. So send that rejected pitch somewhere else and write a brand new pitch for the contact who just rejected you. Stay on the radar. If you have talent, the only reason you won’t break in is if you give up.

Kansas City Comics: Okay, here we are near the end, so it’s time to get philosophical: How would you sum up the most important “big idea” that you’ve learned in life, in or out of comics?

Alex Grecian: This is a tough one. Maybe it’s this: empathize. If you can put yourself in other people’s shoes, you’ll obviously be a better writer, but I think you’ll be better at everything else, too. If you can get inside your boss’s head, you’ll have a better idea of what he wants and how to give it to him. If you can see things from your wife’s perspective, you’ll be a better husband to her. If you somehow grasp what your toddler needs, you’ll be able to communicate with him and head off tantrums before they happen. By empathizing with others, you can become a better person yourself.

And you can create more well-rounded characters too!

–END–

You can read the first issue of online for free at the Image Comics site.Proof

Check out the official Proof message board.

And there’s a ton of Proof content and inside scoop on the Proof fan blog.

Order Alex Grecian’s books from Amazon.Com using these links:

Proof Volume 1: Goatsucker

Proof Volume 2: The Company Of Men

Seven Sons

The Licensable BearTM Big Book of Officially Licensed Fun!

The Factor

24 Hour Comics

(c) 2008 Comics Career LLC and Alex Grecian. All rights reserved.

R. A. Jones is a Tulsa-based writer and editor who got his start in the comics business in the 1980’s. During that time he served as Executive Editor of Elite Comics, wrote for a wide variety of comics news magazines, including Amazing Heroes and Comics Buyer’s Guide.

R. A. Jones is a Tulsa-based writer and editor who got his start in the comics business in the 1980’s. During that time he served as Executive Editor of Elite Comics, wrote for a wide variety of comics news magazines, including Amazing Heroes and Comics Buyer’s Guide. Question 4: What do you do to recharge your creative batteries?

Question 4: What do you do to recharge your creative batteries?